Homeopathy is not a coherent system but a loose collection of ideas, each of which is scientifically unsupported. The most important are the following two:

The similia principle

Homeopaths sometimes call this the ‘Law of Similars’. The inventor of homeopathy, Samuel Hahnemann, may have believed that he’d discovered a natural law when he tested a widely-used malaria treatment — chinchona bark — on his own healthy person and decided that the symptoms he suffered as consequence were similar to those of malaria itself. But ideas of similarity are highly subjective and homeopaths sometimes disagree amongst themselves about which remedy is the true ‘similimum’ for the ailment in question. There is no scientific support for the notion that ‘like treats like’ as a general principle. Experiments conducted by Hahnemann for the purpose of establishing which substances produce which symptoms are scientifically worthless, not least because he used volunteers who knew what they were taking and what effects were anticipated and who also knew each other and could compare notes. Nor did Hahnemann use any kind of control group.

Less is more

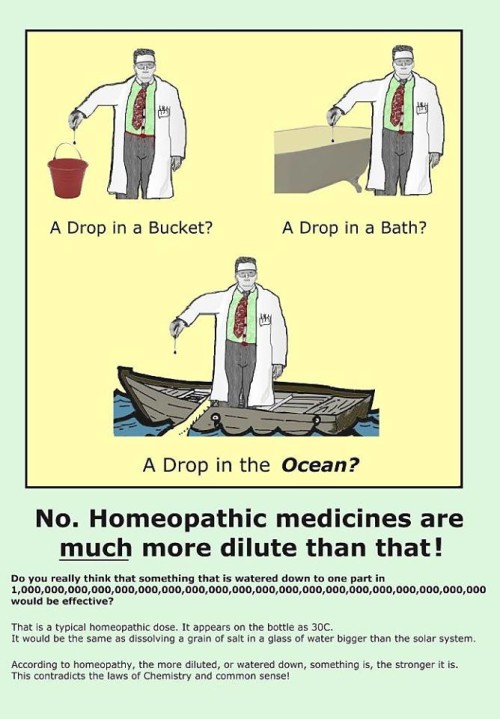

The most controversial aspect of homeopathy is the idea that the smaller the dose, the more potent it becomes. It is sometimes called the ‘Law of Infinitesimals’ but this is mere invention — there is no such law. Homeopathic remedies are typically diluted beyond Avogadro’s number, which means they contain not a single molecule of the original ingredient. Hahnemann routinely recommended a dilution of 30c, which is 1 part ingredient to 1,000,000,000, 000,000,000,000,000,000,000, 000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 parts dilutant. Homeopaths get round the problem of the disappearing ingredient by hypothesising that the memory of the original ingredient is somehow imprinted onto the water it is diluted in, through the process of ‘sucussion’. The question of how the dilutant remembers only the required ingredient and forgets everything else that has ever been in it has been addressed by the suggestion that using doubly-distilled and de-ionised water as the dilutant, eliminates the problem. As there is no scientific evidence to support the notion that water has the capacity to remember and selectively reproduce the effects of matter that it no longer contains, it follows that there is no evidence to support the notion that distilling and de-ionising the water will cleanse it of this memory.

Evidence

“A treatment is considered effective for treating a health condition if it meets all of these key criteria:

- the treatment causes health improvements that cannot be explained by the placebo effect;

- health improvements that occur in people taking the treatment are unlikely to be due to chance;

- the health improvements caused by the treatment are meaningful for a person’s overall health;

- and the health improvement occurs consistently in several studies.” Source

Hundreds of clinical trials of homeopathy have been carried out in many different countries. In 2015 the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council published its report on the most extensive investigation into homeopathy carried out to date. The Council set out to answer the question:

Is homeopathy an effective treatment for health conditions, compared with no homeopathy, or compared to other treatments?

The work was overseen by a Homeopathy Working Committee established by the NHMRC with collective expertise in evidence-based medicine, study design, and complementary and alternative medicine research.

It commissioned a professional research group OptumInsight (Optum) to do a thorough search of published research to find systematic reviews of studies (prospective, controlled studies) that compared homeopathy with no homeopathy or with other treatments and measured effectiveness in patients with any health condition. Studies were considered to be of sufficient size where N>150 (i.e. those studies categorised as ‘medium’ sized or larger).

Systematic reviews analysed numbered 58, containing 176 individual controlled studies covering 61 clinical conditions. Additional information was submitted to the NHMRC by homeopathy interest groups and the public. The NHMRC also commissioned an independent organisation with expertise in research methodology (The Australasian Cochrane Centre) to review the methods used in the overview and ensure that processes for identifying and assessing the evidence were scientifically rigorous, consistently applied, and clearly documented.

CONCLUSIONS: “Based on the assessment of the evidence of effectiveness of homeopathy, NHMRC concludes that there are no health conditions for which there is reliable evidence that homeopathy is effective. Homeopathy should not be used to treat health conditions that are chronic, serious, or could become serious. People who choose homeopathy may put their health at risk if they reject or delay treatments for which there is good evidence for safety and effectiveness. People who are considering whether to use homeopathy should first get advice from a registered health practitioner. Those who use homeopathy should tell their health practitioner and should keep taking any prescribed treatments.”

UK Homeopathy Evidence Check

Prior to the publication of the Australian report, homeopaths would commonly claim that four out of five meta-analyses of homeopathy have been ‘positive’; the British Homeopathic Association made this claim in their submission to the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee inquiry, which reported in 2010. However, an examination of the papers in question reveals this claim to be mendacious.

1. Kleijnen et al, 1991, meta-analysis, 107 trials.

CONCLUSIONS: At the moment the evidence of clinical trials is positive but not sufficient to draw definitive conclusions because most trials are of low methodological quality and because of the unknown role of publication bias. This indicates that there is a legitimate case for further evaluation of homoeopathy, but only by means of well performed trials.

Source: PubMed

2. Boissel et al, 1996, critical literature review commissioned by the European Commission Homeopathic Medicine Research Group, 184 trials. Boissel controversially combined p-values of the highest quality trials to arrive at this conclusion:

From the available evidence it is likely that among the tested homoeopathic approaches some had an added effect over nothing or placebo….but the strength of this evidence is low because of the low methodological quality of the trials.

3. Cucherat et al 2000, used the same data as Boissel but with the addition of at least two more trials. Boissel was one of the four-strong research team and authored the report, which concluded:

There is some evidence that homeopathic treatments are more effective than placebo; however, the strength of this evidence is low because of the low methodological quality of the trials. Studies of high methodological quality were more likely to be negative than the lower quality studies. Further high quality studies are needed to confirm these results.

Source: PubMed

Early in 2010, science writer Martin Robbins wrote:

I spoke to Jean-Pierre Boissel, an author on two of the four papers cited (Boissel et al and Cucherat et al), who was surprised at the way his work had been interpreted.

“My review did not reach the conclusion ‘that homeopathy differs from placebo’,” he said, pointing out that what he and his colleagues actually found was evidence of considerable bias in results, with higher quality trials producing results less favourable to homeopathy.

Source: Guardian online

4. Linde 1997, meta-analysis, 89 trials.

The results of our meta-analysis are not compatible with the hypothesis that the clinical effects of homeopathy are completely due to placebo. However, we found insufficient evidence from these studies that homeopathy is clearly efficacious for any single clinical condition. Further research on homeopathy is warranted provided it is rigorous and systematic.

Source: PubMed

Linde produced a follow-up paper in 1999, which concluded:

The evidence of bias [in homeopathic trials] weakens the findings of our original meta-analysis. Since we completed our literature search in 1995, a considerable number of new homeopathy trials have been published. The fact that a number of the new high-quality trials… have negative results, and a recent update of our review for the most “original” subtype of homeopathy (classical or individualized homeopathy), seem to confirm the finding that more rigorous trials have less-promising results. It seems, therefore, likely that our meta-analysis at least overestimated the effects of homeopathic treatments.

Source: PubMed

Linde co-authored a brief article in the Lancet in December 2005. In it he wrote,

We agree (with Shang et al) that homoeopathy is highly implausible and that the evidence from placebo-controlled trials is not robust…Our 1997 meta-analysis has unfortunately been misused by homoeopaths as evidence that their therapy is proven.

Source: The Lancet

5. Shang et al, meta-analysis 2005, 8 homeopathy trials selected from 110 and 6 trials of conventional medicine selected from 110.

Biases are present in placebo-controlled trials of both homoeopathy and conventional medicine. When account was taken for these biases in the analysis, there was weak evidence for a specific effect of homoeopathic remedies, but strong evidence for specific effects of conventional interventions. This finding is compatible with the notion that the clinical effects of homoeopathy are placebo effects.

Source: PubMed

The Science and Technology Committee published its report in February 2010. It concluded that

To maintain patient trust, choice and safety, the Government should not endorse the use of placebo treatments, including homeopathy. Homeopathy should not be funded on the NHS and the MHRA should stop licensing homeopathic products.

Switzerland

Another favourite report of homeopaths was one commissioned by the Swiss government, which was published in English in 2012. This report is discussed at length here and here.